Johnny Depp as Rochester

Samantha Morton as Elizabeth Barry

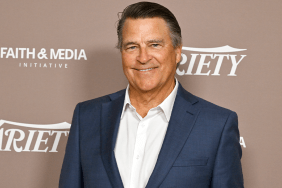

John Malkovich as King Charles II

Rosamund Pike as Elizabeth Malet

Tom Hollander as George Etherege

Richard Coyle as Alcock

Rupert Friend as Billy Downs

Review:

In the Restoration court of Charles II (John Malkovich), debauchery and lack of inhibition truly reigned over all else, but in a land of exhibitionists, one man outdid all others. The Earl of Rochester (Johnny Depp) was a playwright and wit who loved everyone because he loved nothing and was only able to get away with what he said and did – he met his wife Elizabeth Malet (Rosamund Pike) by kidnapping her – because he held the favor of the king.

In a time of great exhibitionism, Rochester – the Great Libertine – was truly the man of his time, the most outspoken and uninhibited of his peers, the high and the low. In many ways, “The Libertine” is like one of the modern musical biopics that have been popping up; a rock star before there were rock stars, Rochester followed the same path and quickly burned out, only in his last moments finding any sort of peace. It follows the same structure of ebb and flow. Helped along by a genuinely fresh eye for period filmmaking and strong performance by Depp, it’s entertaining if not particularly enlightening.

Make no mistake about it, while admirable work is done all around by the supporting cast – of particular note are Malkovich and Tom Hollander as Rochester’s great friend and competitor, the playwright George Etherege – the film belongs to Depp. Rochester – the great lover who hates everything, himself most of all – could (and occasionally does) easily fall into stereotype, the “complicated” man who doesn’t know why he does what he does but can’t help himself. Depp handles the reckless, tasteless side of Rochester with aplomb, but is also adds levels of actual self-understanding in the final act, enough to at least partially dodge the bullet of pointless melodrama. It’s an easy role to make entertaining, but a difficult one to make meaningful and Depp does as good a job as anyone might. His final moments of painful questioning to the audience make great strides towards making everything that came before worthwhile.

The other standout of the film is Samantha Morton as Rochester’s counterpart, the great stage actress Elizabeth Barry. In her story, “The Libertine” rises above Rochester’s often trite story as it examines how she creates a feminist ideal in a world unquestionably ruled by men, mostly men like Rochester. She doesn’t need a man and she doesn’t want one. All she wants is her art and the love of the audience, nothing else. She’ll sell her body to a man – like many struggling actresses of her day – but she’ll never give herself to one. By removing herself from her normal place in the world she empowers herself. Her scenes with Rochester are filled with a tension and meaning that the rest of the film occasionally lacks.

To it’s credit, “The Libertine” is a film that tries hard not romanticize its subject, not in its characterization or in its production. First time director Laurence Dunmore’s vision of Restoration England is milled with mud and murk. The streets are filthy and so are the people, the air full of smoke and smog. Taking a page from Kubrick, it is a very dim film, seemingly lit by natural light only, be it candlelight or the overcast sun, and is filmed largely handheld, giving the film a strong documentary feel. It takes some getting used to and is certainly not for everyone. Being a film, it can’t stay away from fantasy forever, but it tries hard, and that’s worth something.

Slightly pretentious, but original enough to be a bit interesting, and buoyed by strong performances from Depp and Morton, “The Libertine” is a decent telling of a historical footnote, most interesting because of its strong feminist message.