Byzantium: Neil Jordan’s underrated horror film is one of the greatest vampire films ever made

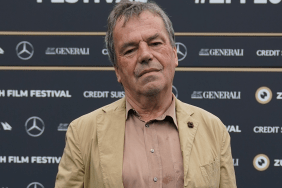

When one mutters about who belongs in the fabled “Masters of Horror” club, the usual suspects are spoken. You know. Hitchcock, Romero, Hooper, Carpenter, Craven, Gordon. All those guys. And yes, they belong in the lexicon of legend. That’s inarguable. But it’s unfortunately rare to see Irish director Neil Jordan‘s name show up on lists like this and I’m really not sure why. Jordan is one of the great directors, full stop. But his work in the genre has exemplified the Gothic ideal and, most importantly, he’s one of the few horror directors who bring a genuine feeling of the fairy tale to his bloody landscapes. He trades in movies about lonely outsiders lost in treacherous but beautiful landscapes and his movies are always propelled by a simmering eroticism that bubbles under the surface of every frame. Look at his 1984 breakthrough movie, the Angela Carter-adapted allegorical werewolf masterpiece The Company of Wolves. With its probings into a young girl’s burgeoning sexual awakening pushed into a Little Red Riding Hood tale of flesh-eating, horny lycanthropes and girls who follow them to ruin, the movie still has no peer. There’s nothing like it. Similarly, there’s few films like Jordan’s The Butcher Boy either, or the troubled but still visually interesting High Spirits or the transgender noir The Crying Game. And certainly, his 1994 adaptation of Anne Rice‘s Interview with the Vampire is not only the best cinematic representation of Rice to date, it’s one of the greatest vampire movies ever made.

But as good as Interview is, Jordan’s bloodsucking best boasts also apply to a more recent effort that sort of slipped through the cracks and is rarely raved about when people wax fondly on the undead. That film is 2012’s Byzantium, a lush expansion of Moira Buffini‘s play A Vampire Story that — like Interview — uses vampirism to unfold a tale of loneliness and the eternal search for people to connect to people as well as nurturing but ultimately toxic nature of family. But here, in this gauzy, sensual phantasmagoria, as in Company, it’s the feminine that feeds the narrative and Byzantium‘s bloody, beating heart speaks of the agony of women and what they must endure to navigate a world that’s been hard-wired by men for centuries to keep them in their “place.” The movie is indeed a masterpiece and it needs more love. So let’s give it some today…

Byzantium stars the great Saoirse Ronan (Brooklyn) as Eleanor, a kindly, quiet and isolated teen living on the skids outside of London who has a sanguinary secret that she’s sworn to keep. While her mother Clara (The Girl with All the Gifts‘ Gemma Arterton, in what is a thus far career-best performance) strips at a seedy local club, Eleanor hand-writes her life story, tearing the pages out of her diary and throwing them to the wind from her slum tenement balcony. When a frail old man collects the scribblings, he confronts the girl, revealing that he’s ready to die… and wants to go by Eleanor’s hand. Literally. Because Eleanor is indeed an ancient vampire and she kills by a growing thumbnail that swells like a phallus when her bloodlust is aroused. But Eleanor is not a monster. Rather, she’s tempered her gift to serve as a sort of Angel of Death to the aged and withered, consensually euthanizing her victims after revealing her true nature.

Truth is something Eleanor craves. She’s carried the weight of her condition for centuries, a dark gift bestowed upon her by her mother and one she’s unable to share. She wants to fit in. She wants a life, even though she knows that’s impossible. She wants roots and companionship and she’s weary of living a lie. Clara, however, is the opposite. The elder vampire is — on the surface — a banshee who kills ruthlessly and keeps her daughter on the run, from mortal authorities and from some sort of secret cabal of men whose aim is to hunt her and presumably destroy her. She prowls the night posing as a peeler and a prostitute, using her eternally perfect body to drain men of their fluids — red and otherwise — and their money so she and Eleanor can continue to move freely through the world. But when Clara meets a sweet, sad John at a carnival who is in mourning after the passing of his elderly mother, she treats him with kindness, empathy. It’s her weakness. As a mother who will stop at nothing to protect her child, she is moved by this man’s condition. Even better, when she learns that he has inherited his late mother’s crumbling seaside hotel/boarding house hotel — the Byzantium of the title — she uses sex and companionship to make the man let her and Eleanor stay with him. Soon, Clara’s set the hotel up as a bordello, where she rescues and liberates street girls and lets them conduct their business in the comfort of the dusty, neon-pulsing palace.

And while Eleanor follows her mother yet again, she has hit a wall and begins writing her life story again, this time with intent to share it with the world. That sad, serpentine story of Clara’s miserable life and Eleanor’s baptism into vampirism is related via alarmingly beautiful and evocative flashback sequences that mirrors the women’s contemporary situation and fleshes out and justifies Clara’s feral, calculated nature. Meanwhile, a sickly young man (played by the always sickly looking Caleb Landry-Jones) has fallen in love with Eleanor and the feeling is slowly, surely becoming mutual.

Byzantium is a marvel. A deep, dark tragedy about forgotten, damaged people who have to scrape and scavenge to survive. And God forbid if said people on the fringe are female, where their bodies are exploited and used for fleeting pleasure and casual abuse and their dreams and hopes obliterated. Such is Clara’s plight, a gentle girl sold into prostitution who endures untold abuse but who finds a purpose and reason to soldier on after the birth of her child and later, is forced to steal her liberation from a sect of male vampires who don’t take kindly to a lowly woman among their privileged midst. But Clara uses her power for one purpose: to protect her child. Always. Forever and ever. And that’s why the gorgeously acted, photographed (by Sean Bobbitt), scored (by Javier Navarrete) and produced Byzantium is really about. The supernatural bond between mother and daughter at what berserk lengths a parent will go to to protect their child. Of course, in life and in Byzantium, there comes a time when the child becomes the parent and when that child begins to pull away to start their own story, the parent simply cannot abide. They’ve structured their lives around a dynamic that was built on protection but inevitably dissolves into control and fear of losing that control. And Jordan profoundly places Clara and Eleanor’s plight high above any simplistic horror movie trappings.

Which is not to say Byzantium doesn’t deliver the frissons. Blood sprays freely, heads are crudely ripped off, wrists are opened, necks torn asunder and — in the film’s most striking sequences — blood flows from a sacred shrine waterfall, bathing newly-born vampires. And despite the film’s focus on feminism, Jordan never shies away from ensuring Arterton’s effortless sexuality is deified. She’s a stunning woman and here, stalking the night in impossible heels and leather pants, or bust-pumping corsets or Victorian robes, she’s an iconic erotic presence. This is a thinking person’s Hammer Horror film, ultimately.

If you’re a vampire cinema junkie and you haven’t seen Byzantium, fix that problem immediately. But you don’t have to be a fang-fetishist to fall in love with Jordan’s evocative masterpiece. This is a movie that demands to be just as immortal as its startling heroines.

Byzantium

-

Byzantium

-

Byzantium2

-

Byzantium3

-

Byzantium4

-

Byzantium5

-

Byzantium6