It’s easy to dismiss a film for being gimmicky. If a movie is shot found-footage-style, some might call it lazy. If a movie is shot in a single take, critics might be harder on production mistakes like a crew member in the shot or a boom mic in the frame. Gimmicks are not a new thing, and they’re not necessarily a bad thing either. Richard Linklater’s Boyhood has a gimmick — it was shot over a period of 12 years, spanning the entire childhood of a young boy as he experiences the ups and downs of growing up. Birdman has a gimmick — it’s edited to look like it was filmed in one take, following a struggling actor as he does his best to adapt a stage play that he hopes will relaunch his career.

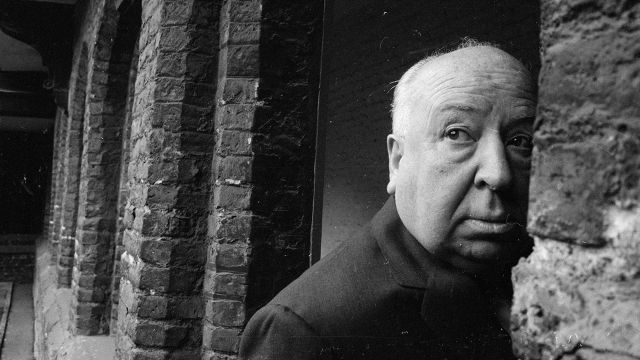

One director who employed gimmicks throughout his career is Alfred Hitchcock. Alfred Hitchcock is one of the last people you’d want to call gimmicky, but he is guilty of using them nonetheless. As Hitchcock proves, gimmicks aren’t the mark of a poorly-made movie. As a matter of fact, a good gimmick used well can completely transform a movie from good too great. Hitchcock has plenty of great ones.

The One-Take

In 1948, Alfred Hitchcock released Rope. The film stars James Stewart and John Dall and is based on a play by the same name. This might explain its multiple gimmicks: The movie uses long takes and plays out in real time to make it seem like the film was shot in one take, just like a play would take place in one (hypothetical) take. It’s also an effective tactic when it comes to creating and maintaining suspense. If there aren’t cuts, Hitchcock robs the viewer the opportunity to catch their breath. It’s an excellent gimmick and one that makes perfect sense in the grand scheme of the film’s tone.

3D

3D is another gimmick that feels new but is actually decades old. Hitchcock used it for his 1954 film Dial M for Murder, also based on a play by the same name. It’s a strange movie to release in 3D, taking place mostly in an apartment, but the effect makes the viewer feel like they’re involved — almost like they’re observing the very tense plot for themselves in person. He even constructed a gigantic phone for a single 3D shot of a finger moving toward the phone to dial a single number. It sounds like nonsense, but it totally works — the only way to see the 3D cut is to purchase a special Blu-ray edition of the film, but it’s definitely worth it to see Hitchcock’s vision fully realized.

Black and White

Black and white used to be the only way to release a movie. Now, ever since Technicolor, shooting in black-and-white is more of a gimmick or a stylistic thing than a necessity. Hitchcock knew this, of course, and continued to use the color scheme well into his filmography (and well after the introduction of color to the medium). Take Psycho, for example: released the same year as such vibrantly colorful movies as Spartacus and The Magnificent Seven, yet shot in moody black and white. It’s a stylistic choice, but it’s a necessary choice: the black-and-white makes the violence feel darker, the motel feel dirtier, and the plot feels shadier.

The Dolly Zoom

One of his most well-known films, Vertigo, uses an incredibly familiar shot for any avid movie-watcher. Called all sorts of things but known most often as the dolly zoom, Hitchcock zooms in while moving the camera backward to create a strange sort of depth-bending effect. It’s incredibly effective and he uses it well. It’s been used famously in Jaws (among many other films), but no one really does it like Hitchcock does.