While the Satanic Panic didnt completely enthrall Americans until the 1980s, occult-themed paperbacks and their ensuing film adaptations proliferated throughout the late 1960s into the 1970s. The changing social tidewomens lib, class struggles, youth subcultures, the fight against censorship in post-war Italy, and Italys period of socio-political unrest known as the Years of Leadspurred an anxiety that cinema was all-too happy to exploit.

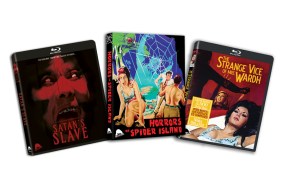

Genre titan Sergio Martinos films are united by a grim thread of sadomasochistic sexuality, unabashed hedonism, supernatural events, and ultra-violent murdersundoubtedly influenced by his home countrys real-life turmoil. Inspired by Roman Polanskis Rosemarys Baby, a 1968 adaptation of Ira Levins novel, Martinos All the Colors of the Dark has a phantasmagorical narrative that unites the giallo with an occult storyline in an alternately urban, Gothic landscape. One of Martinos strongest assets has been his tight-knit group of collaborators. All the Colors of the Dark boasts screenwriter Ernesto Gastaldi (Torso), composer Bruno Nicolai (The Case of the Bloody Iris), leading lady Edwige Fenech (The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh), who was married to Martinos brother, the filmmaker Luciano Martino, and actor George Hilton (The Case of the Scorpion’s Tail), who was married to a cousin of Martinos.

After suffering a miscarriage caused by her boyfriends car accident, Jane (Fenech) experiences troubling visions of murder executed by a steely-eyed lunatic (Ivan Rassimov, The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh). This puts greater strain on her already troubled relationship with Richard (Hilton), who feeds Jane pills to keep the night terrors at bay. We question his intentions when Richards roving eye is drawn to Barbara (Nieves Navarro, Emanuelle and the Last Cannibals), Janes sister, who begs Jane to seek psychiatric help through one Dr. Burton (George Rigaud, A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin). But Janes sexy neighbor Mary (Marina Malfatti, Seven Blood-Stained Orchids) has a bizarre solution to Janes maladies. She brings the doe-eyed Jane to a modern-day Sabbat led by a savage group of devil worshipers who barter in souls (headed a Svengali-like Julián Ugarte, of Frankenstein’s Bloody Terror fame). After a bloody, orgiastic ceremony, Jane is initiated into the group. She soon realizes that she cant escape the Satanic cult after her premonitions intensify, calling her cognizance into question.

Martino and Gastaldis penchant for dark satire is evident throughout the filmhere, parodying the excesses of the Age of Aquarius and Italian genre cinema itself (in a subway scene, one family talks about how violent films are). The directors use of mirrors, objects of revelation, is inspired. He explores atmospheric architectural spaces with dramatic angles and lively cinematography, adding to the surreality of Janes plight.

Most striking is Martinos emphasis on female hysteria, a mental disorder attributed to women dating back to ancient times. Youre weak after that operation, Richard tells Jane early in the movie. Indeed, Jane spends much of the film weeping and wailing for help, drugged and hospitalized, unaware of the power of her own unique abilities. Richard doesnt believe psychiatry can help Jane and calls Dr. Burton a quack. Although Jane suffers greatly after losing her child, Richard is quick to remind her that he shares in her suffering as the unborn babys father. His sorrow feels insincere. Ive already caused him enough difficulties, Jane laments about Richard later on. But it is Jane who saves Richard during the films conclusion, though she still cant accept her own power. I feel theres some strange force controlling me, she tells him.

The wicked cults methods of freeing Jane from the burden of her emotional pain through sexual sacrifices and murder recalls ancient demonological associations between women and sorcery, which accused women of being easily influenced by diabolical forces. The stresses of modern life and a wandering wombstemming from the early belief that the uterus could migrate within the body and obstruct passages, causing diseasewere two purported causes of hysteria. One cure was increased sex and orgasm, enforced and administered by a doctor (usually through digital manipulation). Martino leaves room to suggest that part of Janes disease might be conflicted desireher body, which she eventually offers to the Satanists willingly, entangled by frustrated social expectations and historical trauma.

You have crossed every barrier to reality. You are beyond its limits. And you’ll never see it again, Rassimovs henchman warns Jane. All the Colors of the Dark blurs the lines between dreams and reality. Its a psychedelic nightmare that plays as a kinky cult flick, Satanic thriller, and Gothic giallo, beckoning audiences further down the rabbit hole.

—

Alison Nastasi is a giallo addict and the weekend editor of Flavorwire. You can find her talking about exploitation cinema, VHS, occult oddities, Hammer horror, and other genre fare on Twitter.

All The Colors of the Dark screens in NYC this March as part of Anthology Film Archives The Killer Must Kill Again!: Giallo Fever, Part 2. See the full lineup here.