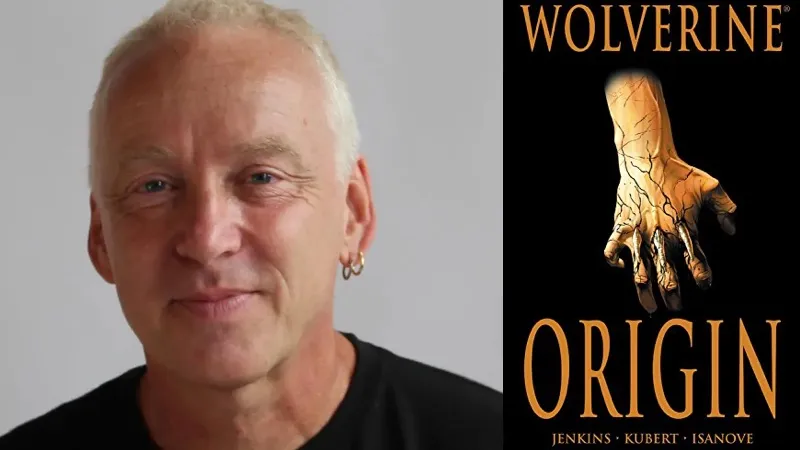

Paul Jenkins is mostly known as a writer of such comics as Wolverine: Origin, Inhumans, and as the creator of the Sentry character at Marvel, but he got his start as an editor for the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and has gone on to write for other great books, video games, and now a ton of his own projects. After running into Jenkins at Dragon Con in Atlanta, Stephen Wilds set down for a long chat with him about his extensive career as a writer and more.

Stephen Wilds: I believe you actually studied acting?

Paul Jenkins: I came from an interesting situation as a kid. My dad was gone when I was very young and it was very difficult to understand where we were going in life, you know? We were certainly extremely poor. There wasn’t really any sense that there would be an opportunity in our lives, you know? I remember hearing about America for the first time and thinking, well you know, I’ll never go there. It’s just not part of my world. I’ll probably stay in the countryside with my family you know, and never get anywhere. You don’t really have a father figure, you don’t really have a mentor to some extent, you just, you go about your life. But I also had a sort of inner motivation that I don’t think a lot of people find. I found it when I was really young. I wanted to do things that were not the things I was currently doing. And so I happened to leave home when I was about 11 years old. I went to a school that allowed me to get a scholarship, a boarding school. When I was there they really wanted this sort of, we want to put you through Oxford and Cambridge and have you be a lawyer and a doctor and that, but I was a creative person and I just wasn’t that person. Instead of really concentrating on some of the things that they probably felt were more appropriate, I studied acting and I liked it and so I left the school and went to study acting in college. I came to America teaching music and drama to learning disabled children. I was really young and I was just working for a summer, basically. I knew I wanted to be creative I just didn’t know which way because I was also playing the guitar, playing in a band. Anything to do creative work but I wasn’t really focused on creativity.

What made you want to work with disabled children?

Learning disabled children really, but the umbrella term of learning disabled here in the States is pretty interesting because it can be people with physical disabilities, it can be kids with mental health issues. It can be any number of kids, any type of kid. I think it’s just one of the things you should probably understand from a relatively poor environment is that it allows you to relate to people in a way because you understand what deprivation feels like, you understand what hunger feels like. You don’t grow up with advantage, you know? I think that just makes anyone who has any disadvantage very relatable.

Who were a couple of your favorite actors?

When I was a kid we didn’t have a television. It’s going to be an interesting part of the – almost always is an interesting part of every interview I do that people are almost always somewhat disappointed. For example, I’ve done a lot of comic work, but I barely know anything about comics. As an actor, I think you look – if you were to ask me now…I’ll tell you this; you know, it’s actually kind of a surprising answer. I’m certainly a fan of Robert Downey [Jr.], I think that what he did and how he has been a chameleon in his career is fantastic, because yeah, he’s known for the Marvel stuff, but he’s played some pretty amazing roles. I think that when you take a look at Judi Dench, is amazing and always has been. She’s just absolutely a brilliant human being who clearly has this presence and I can remember her British sitcoms a little bit.

When I got to study acting, I spent more time down in film school thinking: wait a minute. I love this, writing-directing. That kind of thing made me really happy. That worked for me.

Who do you think the best James Bond is?

I know the feeling I got when Sean Connery was in You Only Live Twice. I really liked the theme song to that. It’s a horrible misogynistic pile of crap, right? But I also know the feeling of seeing George Lazenby when James Bond’s wife got killed. I don’t know, it’s really hard. There have been some great ones. I think probably Sean Connery for me, because there’s no feeling like that, that feeling of that piece of music and seeing my first Bond film.

I always thought John Cleese was amazing, he was brilliant.

As the world’s seventh-biggest Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles fan, I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask you to share some thoughts about your time working with Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird, and ask who your favorite character is.

Donatello, always. I love him. I probably – it’s because I always take the one other people don’t like. In football, in the Premier League, my team is Crystal Palace, that’s the team that no one else has. We’re unfashionable. We’re like the Cleveland Browns. If you love Palace, you’re a Palace fan.

I have plenty of stories. I normally did editing at that point, but it blew up really quickly. When it was really blowing up, I was pulled across. We had a guy in licensing, you know and that was really the big focuses of the offices, and that guy had a relatively heinous set of behaviors. You can only see it in hindsight, right? He had a relatively difficult drug addiction. So, as a kid, I mean I’m barely 20, I’m suddenly thrust into the needed position of trying to kind of control that guy and make sure that some of the stuff in licensing works, calling people up. I can remember these really weird things from it, being on a phone call and thinking, that was some weird numbers they were throwing around, 78 million, and it’d be like, the CEO of Burger King.

I was put in that position and one of the reasons I stayed in that position was, I became really friendly with Kevin [Eastman] especially, I was quite friendly with both, you had to be there. If you only understood what it was like to be there, it was the Wild West as far as the money that was coming in. It was so crazy, the things that were happening around us, around Kevin and Pete [Laird]. They would come into the office, people would swarm them, as if money would fall out of their pockets. There was a lot of bad behavior around it. A lot of really entitled behavior, you can see what happens when people get money. And you’re talking about a kid that comes from nothing. My only thought about this was, it’s not my money, it’s theirs. I never really needed a lot of money. So what would generally happen, Kevin would often come in and walk over to my desk and ask me what was going on. I’d tell him, he’d go cool, man and we became friendly and we’d have fun. I’d go riding motorcycles with Peter Laird around the country. It was interesting, an amazing time. Really fun, and also grotesque.

Any other stories?

Just after Mirage, when I moved to Tundra, the publishing company I did with Kevin. You don’t know what you’re doing at that point. I was 24 or 25 at that point, I’ve got staff, cause I’ve done really well and I was the editor-in-chief there for a while, I was the director of production and licensing. I remember coming back from the set of the second Ninja Turtles movie. Not kidding, right? We’re on the set…

Yeah, I’m not jealous… go on.

I’ve made friends with a load of people, but it was a mess anyway, because they wouldn’t listen. They just did a load of stuff without approval. And I think Vanilla Ice had been there the day before and he’d been acting like a tool. He couldn’t remember his own lines and we shot the song [Ninja Rap] Go Ninja Go and all that stuff and I get on this plane and I’m sitting in first class. Turns out the guy sitting next to me was the CEO of Kroger, the store, so we chatted a little bit and I asked him, I’m in a weird position. I told him what I was doing and how I was trying to do it and I said, mate, I wasn’t trained for any of this. How am I doing? He went, young man, if you ever feel like you want to come work for me, you give me a call. That’s the one thing I really remember about it. I felt like I was doing okay, but it was nice to hear from the CEO of Kroger I wasn’t doing badly.

If they offered to let you do something new with the TMNT property would you?

In all honesty, I don’t think so. It was such a long time ago. I’ve done what I needed to do. I’ve been involved in such a pivotal moment.

At one point the editor-in-chief of Marvel asked me to come back and write the Inhumans. We won an Eisner Award and it was something that was really important to them, because they hadn’t won one in a really long time, so they gave me the keys to the castle, right? I remember talking with Axel Alonso and he said, I’d love you to come back and write it. And I’m like, no thanks. You can’t go backward on stuff, you really have to go forwards, don’t you. I’m not a person that goes back, I love the next thing I’m going to make.

I got to sit in on your panel at Dragon Con where you discussed the book Alters and specifically the lead character, Chalice. What can you tell people about that?

It was something that I wanted to do for many years before I got to do it. I had actually pitched to both DC and especially to Marvel, the concept that if we took people who had a disadvantage in any way. You give someone who has a challenge, and we don’t know what those challenges are, there are plenty in life, and it might be that you have a mental health issue or that you’re physically disabled. It almost came from an idea that I had with The Flash, where I felt like it might be a really interesting story to see what happened when Flash lost a leg. What’s that story? When you potentially just can’t do it, but you give people with a disadvantage a hyper-advantage in the form of a mutant power. So I pitched it to Marvel, loved it, they would never do it. I pitched it to DC, they loved it, but they would never do it. The answer was always, we don’t do new characters. Which, I found to be particularly hilarious because I created Sentry for Marvel and that was a brand new character. So I came in and did my thing, but they would never say yes. That’s a shame.

So Chalice is the main character. The premise is that it’s the near future and people start getting a power that changes them. It’s not the X-Men in a sense, it can be. But it’s also stuff that goes out of control. One person gets the power and blows up half the city, because they don’t know what they can do. It’s similar to the way I approached the Inhumans. Chalice is the main character, she’s transgender. She’s transitioning, and her family sees her as the middle brother of three, because that’s the only way they’ve ever known her. She’s begun the hormone therapy and begun that moment where she’s going to tell her family, hey this is what is happening with me and I’m moving into this phase of my life, and as this happens she gets the power. She’s one of the first people to get it. It gets complicated, she can’t tell her family. I think the secret identity is such a big part of what happens with people who are trans, very often. It seemed like a natural fit for that character.

Let’s be clear, it was pitched a long time ago, but it has nothing to do with the current en vogue let’s do something about marginalized people or have a trans character. I wrote my first trans character in a book in 1999 or 2000, in The Agency. It was a character called Sue that I put in. And here’s the interesting part, it was pretty obvious she was a trans character, we just never said she was. Why should we? That’s a character that happens to be trans. There’s no sense in making her transness part of the story all the time. The issue of transitioning did fit Chalice. Why I love that character so much, is that she then becomes the person who helps people who are going through this power and she helps them transition into their new identity. So she’s the one person who has the heart and understanding of what it must mean to transition, and yet she cannot transition with her family yet, so she can only be herself when she’s in costume.

Alters is about lots of people with disadvantages. There was a story about a homeless woman with two children, she gets the power and she can teleport through glass, any reflective surface, it is super powerful, but she can’t even feed her two kids. So what do you do? A mom and two boys that can’t eat, it’s my story, the story of my childhood. It’s the way my brother and I grew up at times. What Alters became is this really powerful story and I had these amazing interactions with people at the shows. We had a character with Cerebral Palsy, and I had someone come up to me who had CP and they said thank you, now I have my character. I was so moved by that.

I had a number of interactions with trans people at first, you know there was a lot of reluctance. I think a few people said, you can’t be the guy writing this, but my response to that is, I will always learn. I will always make sure that I try to learn. I will do my best to be diligent. I ran each book by about six different trans people, who helped me read it and understand what I was doing. Surprise, surprise, they all had different stories, so there’s no one way of doing it. So it was fascinating.

Let me tell you how hard it was. I had two or three fellow writing professionals who said, I wouldn’t do that if I were you. I can’t even comprehend not doing a story because you’re supposed to be afraid of it. Now, I understand what the potential issue was, you’re not the guy to write it because you’re not the authentic voice. Well, here’s my disagreement with you. I don’t agree because we’re human beings and my job is to understand the human condition and talk about that. I’m driven by story, not by gender identity or an agenda, or trying to make sure that I am sensitive all the time to what may be going on with someone who is transitioning.

I learned one thing from this project, which is to stand up for myself. I was on a call about this today, about Alters, and I really believe this. I learned an awful lot from some of the trans people I worked with, and I think they learned something from me too. I think they learned, that despite some of their reservations, yes, we all have each other’s backs in the terms of storytelling, and I could tell that story. That was very fascinating to me and very validating.

I know you’ve done some writing for film and television, how do you feel about the stuff you’ve done in those mediums?

I love film and it’s probably what I should have done, but I did not take that path, you know?

A lot of your work and ideas in comics, like Wolverine: Origin, have made it into scripts and appeared on the big screen. How do you feel about seeing those works brought to life?

Not as positive as you might think, I’m not really that into it to be quite honest. I feel like a lot of my work has been used but no credit has been given. You know? I made a lot of stuff for them. When I went to Marvel they were in Chapter 11, this close to Chapter 7, and a lot of what I wrote helped propel them out of bankruptcy. I got a call from Joe Quesada when he was editor-in-chief, and he said, hey good news, they really like the way you wrote this interaction between Peter Parker and the Green Goblin. I just felt the Goblin would look at him and say, I want that guy, I want that guy to be my son and heir cause the other one is a drug addict.

So they brought that into the film, and they told me they were doing it and said they were going to line me up with some interviews. Then all of a sudden, it changed, and they said, well actually, we can’t do that with you because there’s a contractual thing where Stan [Lee] is the only person that can get mentioned, so there’s no thank you, there’s nothing. And I said, “Okay, I suppose,” but then they did it again, and again, and again. Then I created the origin of Wolverine and didn’t get mentioned in any of those stories, so.

I was pretty vocal about it and said it. I don’t like the bullying of creators, I don’t think it’s right. I think creators get treated really badly. I just don’t think it’s correct. It should have never happened, and it should never continue to happen, yet it has persisted. So when I had that to say, I made two mistakes. One was that, I was very articulate, instead of going on a Twitter rant. I actually said it in a fair and manageable way, but that’s not going to fly. Don’t be articulate, because it really pisses people off. If you go on a rant, it’s different. They almost expect some of the creators to do it. The second part was where I stood on the battlefield and thought, okay, I’m going to take a step forward, who’s with me? And everyone else took a step back. I thought, well, that’s unfortunate.

So you worked on the Black Adam comic and now Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson is about to bring him to life on the big screen. How do you think he’ll do and what do you hope they take from the comics for the movie?

Oh, I think that was a really good choice, actually. I think it depends on whether or not they have The Rock just be The Rock on camera, or if they actually do something with the story, it just really depends.

What was happening to Black Adam, what he pointed out to his people – and I respected this – was that he really pointed out to his people that, you can’t have me fly in and fix it. This isn’t about me putting an umbrella over this country, this is about us working together to take this challenge on, and he’s right. You don’t want me to just save you all the time. That just creates a thing that doesn’t help the country. What helps you, is that we join together to solve this problem. I like that concept because it was the action of a true leader.

What drew you to working on Hellblazer and the character of John Constantine?

Well I mean, that was my first real gig in comics. I had this weird moment where I had been an editor for Neil Gaiman, and when I was at Tundra I was Alan Moore’s editor, and I had gotten to know Alan and he was doing big numbers – that was amazing. I sat with Alan in his house at one time, we were talking about how he wrote stories, and I’d been thinking I might like to do this, I just didn’t think that comics represented the standard of storytelling I thought they should. I had never written a comic. I listened to what Alan said and I thought, that’s interesting, Alan thinks about it this way, and that’s the way I think about storytelling. It kind of gave me some confidence.

So I walked off to San Diego Comic-Con and met the editor of Hellblazer and I said, any chance I could try out for your book? He said, what have you written? And I admitted I had never written anything before, and six weeks later I was the writer of Hellblazer.

My brother is still from the country, punk. Rich the Punk is my brother, so the characters that I had in Hellblazer are all my family. All the Crusties, like Rich, Michelle, and Syder, and the friends and stupid people, those are just all the people I knew from Britain, the Pikeys and lunatics.

Have you seen the Keanu Reeves’ Constantine movie?

Yeah, I liked it. I actually liked it, I thought it was good.

What about with Matt Ryan from the television shows?

So he is [great], but I didn’t like the series at all. I thought it was the opposite of what Constantine was about. John Constantine doesn’t have a power, he doesn’t do magical recitations to get what he needs. He doesn’t throw pixie dust up in the air to follow it, which is what they had them doing all the time. He looks the Devil in the eye and the Devil blinks. That’s how you do it. They just didn’t have the guile writing that type of story, that kind of story that I would write or Garth [Ennis] would write.

Who do you feel is the best Spider-Man villain?

[Laughs] It’s interesting, right? I was lucky enough to write the Green Goblin a lot of times, and I do think the interaction between them – I know we wrote a project called A Death in the Family that a lot of people have seen being one of the ones that really speaks to them, because you find out how close [Peter and Norman] are really, in some ways, and how the Goblin will do a thing that Peter will never do. And Peter won’t do it, not because of Mary Jane, but because of Gwen, and I thought that meant something, that story.

I wanted to write some comedy ones, and I’d occasionally do them and it was fun, but one of them was The Big Wheel. I really wanted to write The Big Wheel, and it was just about a day that was really chaotic because he gets a concussion, and he can’t keep up. It’s a really funny story. …][Laughing] I wanted to say his name was Axel. …]And the other one I wanted to do was the Hypno-Hustler, which is a dude that would hypnotize people with his music.

I don’t look back and re-read my work, but if I ever re-read the Venom story I did with Humberto [Ramos], that was a pretty effective story. You felt for the guy in the end. You understood his torture and his pain.

You did a stand-alone issue with Commissioner Gordon a while back, do you enjoy writing for singular or smaller characters?

I do, always have done. My big thing is single-issue stories, I love single-issue stories in the mainstream. Because we just don’t do any of them, and we should all the time and we just don’t. We do these big decompress things that take eight months, and I’m like, I could have written that story in a month, you know?

Do you feel when studios translate comics to film that they should keep the more mature material close to its original form or adapt it to include a wider audience?

I think a story is a story, and if you have something that speaks to you in a particular way, stick to it. Don’t go trying to homogenize, don’t go down a certain road because you think something is needed. I don’t think that’s a good idea. If it’s all ages then write all ages. People try to fit stuff in just because they’re not trying to write the story, and sticking true to the story, they’re trying to write a piece of marketing, and that’s a problem. I would always advise people to be true to what the story is intended to be. These are marketing ideas though, like, we don’t think we can sell to an audience if it’s PG-13 or above, and I understand that, it’s a moneymaker for them.

Your career in comics is already amazing, but you’ve also written for movies and video games. What has made your career across these different mediums so successful and how did you transition so easily?

Story is everything. Story, characterization. Do not start it unless you explain why it deserves to exist. If you can’t explain, don’t do it. What I love the challenge of – is finding something like game work – and I heard when I first started working in games was, it can’t be done. That means the person telling me, it can’t be done, can’t do it. But I can. That’s not arrogance, I promise. Try telling me I can’t do something, that will really be my Marty McFly response, okay, now you’ve told me I can’t do something, that just means you can’t do it. We heard a lot from the industry itself all the time back in the day, it can’t be done, stories can’t be told in games, and now that seems absurd, but that was because we hadn’t done it yet. … Mid ‘90s I think, it was always, you can’t do story in-game, you can’t do story in-game.

The interview continues on the next page with Jenkins discussing his work in the video game industry, including his planned ending for The Darkness.