Visionary filmmaker discusses the MOREAU doc LOST SOUL and his plans for Lovecraft adaptation THE COLOR OUT OF SPACE.

The tragedy of a young artist first enticed and then crushed by the Hollywood money machine is nothing new, yet theres likely no more heinous instance of this sort of tinseltown trampling than with director Richard Stanley and his experience on THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU

Its the mid-nineteen-nineties, and Stanley was poised to realize a lifelong dream. After earning strong critical notice and an underground following over his debut sci-fi shocker HARDWARE, and having just emerged from a heated tussle with Miramax executives over the final cut of his mystical serial-killer head-trip DUST DEVIL, Stanley stood on MOREAUs Australian coastline set, ready to roll cameras on a modern and daring cinematic update to H.G. Welles queasily prescient novel of biological hybridization. Two-and-a-half days later, he would be fired.

My actual demise on the project came after an attempt to shoot a sequence on a freighter off of Cape Tribulation, which was involving a puma and a bunch of other things, Stanley recalls. It was kind of my LIFE OF PI moment. It was a very simple sequence, and I think all the ways in which we were defeated in completing that sequence would make for a good LIVING IN OBLIVION-type of object lesson. We were on board the freighter with a bunch of live animals, Val Kilmer, and other cast members. In the opening scene, the cast-away wakes up in his cabin, surrounded by these different rare specimens, tropical animals and cases of medical supplies, and he hears a grotesque animal voice reading from outside the cabin. Its actually MLing (Marco Hofschneider), the dog man, who is practicing his English and trying to read from a copy of Shakespeares plays. Hes reading to the puma on the front deck. The cast-away hears the voice and leaves the cabin; he wanders across the deck and the dog man turns him, to reveal that hes horribly deformed. The cast-away recoils and bumps into Val Kilmer. That was the scene we were trying to shoot. But between an (oncoming) hurricane, and Val taking an exception to why the other character should have all the dialogue in the scene, why it should be the dog man and not him reading Shakespearethat leading to why the Dog Man be in the scene to begin with, during which time the wind was rising and the freighter lurching from side to side. It was a very simple sequence, but after two and a half days, we were pretty much broken. And as a final indignity, and perhaps a cutting metaphor for his overall treatment on MOREAU, Stanley adds, As the storm rolled in, I first evacuated the actors to the mainland, then wrapped out the crew. Some of us stayed on the ship to get the animals ashore; while we were moving the puma cage from one ship to another, I was underneath the cage, trying to stabilize it, and the damn animal pissed all over me (laughs). It was our fault, the puma was terrified.

Stanleys unceremonious dismissal is the subject of director David Gregorys acclaimed documentary LOST SOUL, a tragi-comic investigation into the startling details on just how the MOREAU production spiralled inexorably out of all control, and how the centrifugal motion sent Stanley flying off of his passion project. Ive made a lot of documentaries on the making of films for DVDs and what not, but this is definitely the most insane, says Gregory. (SOUL) has cast a lot of attention towards Richardthat he was this visionary that has kind of disappeared from the scene for a long time. While having not exactly disappeared, Stanley subsequently took up residence in a remote area high atop the French Pyrenees, thus creating the romantic aura of an artist in self-imposed exilewhether intentionally or not. For the last many years, Ive been living in a very isolated place, says Stanley. I guess I got too far into the MOREAU movie and ended up like its lead character, living very far away from human beings. I will be visiting America next month, and checking out what the twenty-first century is like. It should be noted that Stanley has hardly been professionally idle in the years since MOREAU, saying that Over the last twenty years, Ive been basically sustaining myself with gun-for-hire screenwriting and script-doctoring work, and I havent been too picky about the projects Ive worked on. Hes also been linked to a number of directing jobs in the intervening years, including the Stallone-starring JUDGE DREDD and, ludicrously, for SPICE WORLDthe frothy attempt to secure movie stardom for plastic pop act The Spice Girls. Today, Stanley can only laugh when remembering some of the odd projects that have seen his name attached over the years. I also did a script treatment for a sequel to (1978s) THE WILD GEESE, which is another completely anomalous one. It was meant to be a vehicle for the Roger Moore character, and one of the more unlikely things Ive written.

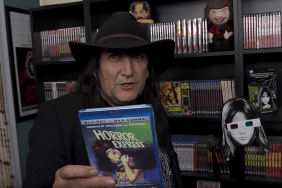

After making a well-received preliminary comeback through his contribution of a short segment to the 2011 anthology film THE THEATRE BIZARRE (An adaptation of Clark Ashton Smiths Mother of Toads, starring Catriona MacColl of THE BEYOND), Stanley is now set to return to the big screen properly by writing and directing another take on a beloved piece of classic literature: H.P. Lovecrafts THE COLOR OUT SPACE. Weve actually been trying to bring a version of COLOR to the screen for a few years now, he says. This process started after the THEATRE BIZARRE short, where we realized we could turn around a twenty minute short for twenty grand on the five day schedule that we had. The thought of trying to do a feature-length Lovecraft adaptation kind of seeded in us, and I started working from there. Were hoping that this year we might get the wherewithal to actually put it together.

The public domain status of Lovecrafts COLOR text has made it an attractive basis for a number of frugal filmmakers, a fact Stanley acknowledges: Its obviously a Lovecraft story thats been done a few times before; I think you get one COLOR OUT OF SPACE every couple of years. We had the German version, DIE FARBE, last year, and Ive noted at least one rival low-budget production out there at the moment, but each (adaptation) is so distinctly different. The approach Ive been taking is to try and return to the source, to root the thing in cosmic horror. Lovecraft persistently said that all of his stories were aimed at trying to evoke a sense of cosmic terror in the reader, and thats something that Ive never really gotten from a Lovecraft movie. The movies end up being generally very campy and endearing. They dont really threaten my soul in the way that maybe an Ingmar Berman or a Tarkovsky movie would, so Im taking a somewhat more adult approach in conveying the Old Ones. Gregory, who has been privy to pre-production details and designs, adds that Anyone who knows Lovecraft and has read (Stanley)s script thinks that COLOR could really be the first adaptation of his work that is pure.

For me, Stanley continues, I find more Lovecraftian moments in non-Lovecraft movies, John Carpenters THE THING being an excellent example. On the arthouse front, theres a scene in WINTER LIGHT, the Bergman movie, where the girl has a vision of God as a spider which is scuttling down to eat her. I guess that the first thing is that the stories themselves dont lend to easy adaptation. I mean, Lovecraft had almost no interest in characters. His human characters appear incidental, and their actions are largely meaningless. They are rarely able to achieve anything at all; they mostly panic and go mad in the face of whatever is happening. This makes things kind of unsuitable for a Hollywood approach. I guess that the second problem is some kind of unconscious fear of the material, in that we tend to shy away and make fun of the Old Ones, or make it kind of cuddly, because its possibly too scary to look at them straight up. I mean, I actually have a plush Cthulu doll on my bed, like a lot of folks! (laughs)

So why attempt COLOR specifically? Stanley says, Its dealing with things that exist beyond our colour spectrum, and our audio spectrum, so Im trying to get these ideas of ultrasound and infrasound, things that exist beyond ultraviolet. That naturally takes you into some disturbing and disorientating material, which means you can create an audio and visual texture that makes the film into something like a bad trip. Ive always structured my films that way: something that takes the audience slowly up and then takes them beyond where they think theyre going to go. On the more practical front, its one of the few Lovecraft stories set in a single, confined location, in the backwoods Arkham and largely on a farm, and doesnt involve a city of the Old Ones hidden beneath Antarctica or sunken Rlyeh at the bottom of the Marianas Trench. Its kind of more accessible. It was a toss-up between that and THE DUNWICH HORROR, because, personally Id love to see the Whatleys brought onscreen one day, as a kind of proper backwoods degenerate, GREAT GOD PAN crossed with the TEXAS CHAINSAW family, type of way that you would imagine.

At the time of this interview, financing for COLOR was yet to be secured, and Stanley was soon to make the above-mentioned trip to Los Angeles in hopes of doing so. This week saw the welcome announcement that Elijah Woods SpectreVision has stepped aboard the project, an admirable move as Stanley is keenly aware that the bleak despair and pessimism found throughout Lovecrafts oeuvre doesnt exactly scream of commercial potential. At the moment, its still a dearly-cherished ambition, he says. Id like to keep (COLOR) on an independent level if I can. The script has already done the rounds at one studio that I wont name. The general perception was that the relentless, horrific aspects, and the downbeat ending, have made the project into what they would consider a niche film. It would also affect the level of gore and sexuality in the thing. So I could see that there would be a conflict in going to a studio, where youre automatically going to have people giving you a hard time over killing children or killing the dog (laughs), so at some level I think were better off staying as an indie movie. Hes also hoping that roping in some familiar cohorts will speed along the process: Were assembling the old team, a lot of the old crew that I havent had the chance to work with for a number of yearsnotably Bruce Spaulding Fuller from the Stan Winston Creature Shop, who was one of my main creature people on THE ISLAND OF DOCTOR MOREAU. Hes been diligently creating designs for the various fusions and mutations on the (COLOR) farm. Stanleys enthusiasm is palpable, and he assures that COLOR would mark entirely new territory for him as a filmmaker. In a way, Ive never made a horror movie before, he says. I have the desire, on this side of death, to do one movie which is determined to scare the audience. Both HARDWARE and DUST DEVIL are kind of genre hybrids, but theyre not primarily horror movies.

As exciting as the news of an impending Richard Stanley feature might be, theres an additional project in the works, this one arriving with some measure of justice: Im currently hard at work on re-writing a new draft of THE ISLAND OF DOCTOR MOREAU, crazily enough, Stanley announces. Thanks to LOST SOUL, theres been a lot more interest again in the original story. A French comic book company, the Humanoids association, has engaged me to turn the original movie (script) into a graphic novel, with an eye on then adapting the graphic novel back into a movie. Its a process that they guess will take about five years. As explained in SOUL, Stanleys eventual MOREAU shooting script included contributions from writers Michael (APOCALYPSE NOW) Herr, and Walon (THE WILD BUNCH) Green, though Stanley doubts their input will remain in the comic version: The nice thing is that Ive been able to go back before (Herr and Green), and create an improved version of the first draft with twenty years of hindsight, because I realized I was making a lot of decisions based on the dictates of my corporate masters right from the beginning. Obviously, with the graphic novel and the potential of VFX these days, you could do a lot of things that we couldnt dream of twenty years ago. So that side of it is extremely liberating. Ive gone back to the version of (MOREAU) which is set shortly after a global thermonuclear war, and Ive expanded on the beast people so that they now include plants and cetaceans.

And what of the MOREAU film as it now exists? As soldered and stitched together as it was by replacement director John Frankenheimer, a filmmaker reportedly hostile and dismissive toward the material? Asked if there is any glint of his designs or personality remaining in the released cut of the film, Stanley claims none of it. Its completely compromised, he says. Its the difference between a lucid dream and a nightmare, in that with a lucid dream, youre in control of what happens, whereas in a nightmare, things still seem familiar but theyre all in the wrong order and come at you in a terrifying way.

By the time (star Marlon) Brando got to set, Id been off the project for a while and I dont think even the makeup effects were being supervised, Stanley continues. I get the sensation that the effects artists were being pretty much left to their own devices, in that most of the designs left in the finished film have gone in different directionsdirections that dont always seem to be coming from the right place. Decisions to tone down a lot of the makeups, so that the dog people no longer look like dog people, having lost their snouts and pointy ears. Probably all what remains from me are the locations: The house itself, and the aeroplane graveyard in the middle of the island. That, plus some of the castingRon Perlman, Fairuza (Balk) and some of the people who came on-board when I was there.

Speaking of Balk, she appears in the LOST SOUL documentary as a staunch defender of Stanley and what he originally intended to create with MOREAU, and she forcefully debunks some of the scurrilous slander thrown at Stanley throughout the course of the doc. Its a stance that Stanley certainly appreciates. Yeah, absolutely, he says. Im a staunch defender of hers as well. Were hoping that SOUL and the MOREAU business working its way out will lift a little bit of a shadow from our lives. And is there potential for the two to reunite once COLOR reaches the casting stage? Im really fond of Ru, and that makes her very hard to cast, laughs Stanley. I mean, I wouldnt want to cast her as the mother in COLOR, because such terrible things happen to her! Id really hate to have to do that to Ru, and I wouldnt want to put her back into makeup again.